By: Jessica Carreiro

Hidden in a deserted nondescript industrial park in Huntington Beach is a warehouse with something inside that is far from ordinary. Women in fishnets and quad skates speed around a wooden track pounding each other around under alias’ like Princess Slaya. This is the all girl revival of roller derby: a sport, a show, a feminist movement, and for these girls, a lifestyle. Part of roller derby culture is replacing the name you were born with, your government name, with an irreverant nom de plume. Some girls choose to put their spin on pop culture references with names like Skatey Gaga, Chick Norris, and Darla Deville. Others prefer more intimidating names like Indian Burn, Char Mean, Hell Toro, and P.I.T.A. as known as Pain In The Ass. The rest pick names that fit their personality like Ruby Rocker, Motown, and Ivanna Cocktail.

On April 19, 2011, the Orange County Roller Girls are huddled up by one of the warehouse’s expansive white walls. They begin every practice this way: sitting between a large, wooden banked track and red electrical tape on the floor that serves as the flat track. You can play derby on a flat track or a banked track. Banked for all 360 degrees, the steepest angle of the bank track is elevated over 4 feet from the ground. Although, when tumbling over the protective rail at speeds of 10 to 15 miles per hour, it feels farther.

As they talk, they take off their everyday gear and slip into their pads and customized helmets. However, because today is picture day, they leave their helmets and pads on the floor with their sports bags and purses. Like girls at prom, they watch to see how the next girl to walk into practice did her hair and makeup. Before the picture, they go into the bathroom to make last minute alterations. Looking into one of the three mirrors, a girl with the name Jabberwocky printed on the back of her shirt sighs and whips her short hair into two pigtails on the top of her head, “I’m not going on the banked track today. I have a love-hate relationship with that thing, and it’s been a rough past couple of days--I just don’t feel like having a bad day on the banked track.”

The picture only takes a few seconds. They know the drill. Tall in back, short in front. Smile. Click.

As they disperse, they pull their hair back, put their helmets on, and get ready to skate. The girls need their pratice. In just under a month, the OC Roller Girls will be the first to bring a banked track roller derby event to the city of Anaheim in over 30 years. The game, or as it’s called in derby, “the bout,” has to go off without a hitch. One of the founding members of OC Roller Girls, Mia Roller, government name Elena Parra, knows how much work has gone into the banked track. “We’ve been working on it for months. We built it ourselves.” she says, “Everything, from every nut, to the paint, to the materials. I think it took us about four months. And that’s one of the fastest that’s gone up.” Using a Kitten Traxx blueprint, they planned the construction. Derby girl D’Cup Runith Ov’r #33D, and her boyfriend, ref, and carpenter Cameltron headed the project. Everyone chipped in where they could spare the time from work and outside life, and eventually it was finished. The wood is painted gray to look like cement. The black padding that covers the safety rail matches the steel rods that elevate the track. Each of the 44 pillars that hold up the top bar of the safety railing are marked with an orange stripe. The girls wanted the track that they’ve dreamed of skating on for 10 years to be covered in orange and black: their team colors.

Roller derby started out in the 1880s as endurance races. Races lasted up to six days at times resulting in death from exhaustion. In 1914, the six-day race of the past was transformed into a 24-hour marathon. Leo Seltzer, credited with helping to craft the sport into what it is today, tells Pop Cult Magazine that the major turn for the sport came when he and famed sports writer, Damon Runyon, realized the crowd’s appeal to illegal conduct. When the fast skaters attempted to break free from the pack and lap the slow skaters, the pack would join together so they couldn’t pass. “At first they didn’t want them to do that,” Seltzer recalls “but then people liked it so much, they kind of allowed blocking.” So Seltzer and Runyon decided to make a new roller derby. One for the people.

Instead of long marathons, the game is composed of a series of short sprints, called jams. During a jam, a whistle releases a pack of eight people, four on each team. These are the blockers. A second whistle, shortly after, signals two jammers waiting 20 feet behind the pack. Once the jammers catch up to the pack, they must squeeze and shove to fight their way through. The first jammer to break free is dubbed lead jammer. The jammers race around the track until they are met again by a wall of blockers. For each blocker of the opposing team a jammer passes, they earn a point. Jammers have only two minutes to accumulate as many points as possible.

When roller derby was at the peak of its popularity in the 60s and 70s, derby leagues made up of male and female teams traveled to stadiums of sold out crowds in every major city. The phenomenon was televised in the popular series Roller Games. Part of derby’s success was its ability to cater to the audience. The skaters knew people wanted to see them fight, so they staged fights in which the crowd favorites pretended to get angry and knock each other off the track. The constant thrills and spills of the game captivated the crowd. Despite the game’s widespread attraction, the show was canceled, and the sport began to die out by the late 70s, early 80s. It wasn’t until 20 years later that the sport was seen again, but it wasn’t the same as when it disappeared.

Today’s roller derby is more than a sport, it’s a feminist movement. In Orange County, the OC Roller Girls recruit and produce strong women. If you base your knowledge of Orange County women on the reality T.V. show, “The Real Housewives of Orange County,” you might be deceived into thinking that Orange County women spend their days gossiping about their neighbors to their plastic surgeons. That’s not the first impression you get from derby girls.

It’s difficult to pin point exactly what’s so intimidating about these girls. It could be the height advantage they get when standing in their two-inch high quad derby skates. Or it could be that with their sleeves of tattoos and the rough, but funny way they have of insulting each other, they seem like the kind of girls who could have a usual at a biker bar. Yet, after spending some time with them, it’s clear that what’s intimidating about them has nothing to do with their physical appearance. Rather, it’s their confidence. Their complete lack of insecurity about how they look, what they say, and what they do.

For Mia Roller, the banked track is what saved her from losing her passion for the sport. A mother of two, one 10 year old boy, Nicolas, and one 17 month old girl, Bella, Mia found her priorities shifting after she had her baby girl. Derby was less important. All the girls are forced to pay membership dues, but there’s no requirement to go to practice. The incentive is more game time, but as a woking mother, she’s got more on her mind than trying to make the A-team. “I think that’s how I’ve kind of progressively move down teams. You know, less committed. After I had the baby, I was a mom. When I was on the A-team, it was kill, kill, kill, derby, derby, derby. You know, my kid was ten and he could just hang out. But, you know, having a new baby, my commitment is just--I can’t get through as much. I love it, but I’m not in love with it like I used to be. So the priorities changed.” Now her priorities are family, work, and church. “Derby kind of fits fourth. Because then you have your friends. We call them NDFs. Your non-derby friends. Your NDFs suffer because you’re like work, kids, life, work, derby, work, church, and, oh, somewhere in there I can fit you in for lunch at 2 o’clock on Thursday.”

It would be easier to quit derby. There are plenty of less time consuming hobbies and forms of exercise. She tried the gym. She tried kickboxing. But nothing sucked her in like derby. She remembers as a kid sitting in front of the television watching derby games. Even in the 70s, when her mom asked her what she wanted to be in life, she’d say, “I wanna be a derby girl!” Skating was already a part of her life. She competed as both a figure skater and a speed skater. However, a knee injury when she was 14 took her out of competition. “ And then after that, you know, I was just a normal teenage kid. I was 14 when roller blades came out and then it wasn’t cool to be on quad-skates because everyone else bladed. I just quit.” It wasn’t until about 2004, that her mom heard about women starting up a roller derby league in L.A. on the news and told her to check it out. The L.A. Derby Dolls were the first all-girls roller derby revival league to hit southern California. They were passionate, organized, and quick to get a bank track. The only problem was that they were in L.A. She was going to school at O.C.C. and working two jobs. She couldn’t move, and driving to L.A. twice a week for practice adds up. Her childhood dream was just a county away, but it was impractical.

One night while scrolling through Craigslist, she came across an ad looking for women in Orange County who wanted to skate. She decided to check it out. Her and four other girls met at the Holiday Skate Center in Orange. They skated around the rink for a session. It wasn’t much, but it was the beginnings of roller derby in Orange County. Six years later, 200 members are proud to be a part of the Orange County Roller Girls.

With only six practices left until the banked track debut in Anaheim, the girls have a lot of work to do. Not only do they have to perfect their banked track technique, but they also have to stay conditioned for flat track games. Disco, head of OC derby, has wanted a banked track for a long time, but now that she has one, she also wants to maintain their flat track teams. They have three flat track teams that vary in skill. The A-team is Blockwork Orange. The B-team is The Wheel Housewives of Orange County. And the C-team is Pulp Friction, the team Mia skates for. These teams travel all over the states to bout in cities like New York, New Orleans, and San Francisco. Their two banked track teams are Orange Whip and The Traffic Jammers. As homemade signs decorating the walls of the warehouse will inform you, OCRD is “bi-tractual and proud.”

Before breaking into teams to scrimmage, head coach Bryan Hunt makes the girls skate some warm-up laps. He’s one of a handful of men that regularly attend practice. Another is Quadzilla, or as Mia refers to him, “That awesome black guy all the girls want to skate like.” He helps coach the girls when he can. On the sidelines are Mia and Beantown Brawler’s sons who are similar in age and spend most of their time walking around the warehouse, the parkinglot, and picking on Beantown’s husband. This is a favorite activity of the girls as well. Sitting in a lawnchair he brought from home, Mr. Beantown chats with the girls who can’t practice due to injuries and cheers on his wife. Always smiling and very sociable, Mr. Beantown is an easy target for the girl’s ridicule.

When the girl’s focus becomes more on their jokes than on their skating, Bryan knows how to get their attention with his own brand of humor. He frequently comes up from behind girls not paying attention and gives them a shove. This usually results in a yelp and an awkward flailing of the arms and jerking of the hips as the girl desperately attempts to regain balance. Bryan laughs grabbing his stomach.

Although the girls love to kid around, once the scrimmages start, the joking stops. They’re well aware that in two weeks, their rivals, Long Beach Roller Derby, will be having their first banked track event. Though the two leagues share many of the same coaching assistants and refs, there is still some feuding between the girls. Mia explains, “Long Beach is kind of the unspoken rivalry against everybody because they’re new and they’re kind of doing their own system. Their banked track’s a little different. Their rules are a little different. And there’s some renegade leagues out there that say, ‘We play by no rules.’ So, to us, that’s kind of like we’re athletes and you’re WWE. There’s always going to be the ‘we’re better, no we’re better’ aspect to the game. But its pretty much off the track. But with Long Beach it’s kinda--different teams have different personas. Just like different girls have different personas. There’s the cool girls and the dorky girls and the mean girls. Long Beach is kinda,” Mia tosses her hair and scoffs in imitation, “‘We’re Long Beach, we’re better.’ I mean don’t get me wrong, I love them to death. Some girls have more drama with them than I do, but yeah there is definite, ‘We’re Long Beach, we’re tougher. We have more street cred.’ You know, and we’re kind of,” she perks up with a big smile and tilts her head to the side, “‘We’re Orange County.’”

On April 22nd at the Queen Mary Dome in Long Beach, two lines of people, each a city block long, wait to be let in to the kickoff banked bout of the LBRD season. Standing outside a huge white dome, former home of the Spruce Goose, next to the even bigger Queen Mary cruise ship, it’s an odd setting for a derby match. The group of impatient soon-to-be-spectators looks like a cross between people you’d find at a hockey game and people you’d find at a punk concert. Harsh winds and increasingly dark gray skies make the young crowd of people in their 20s and 30s antsy to get inside. Half an hour over the scheduled “doors open” time, the doors finally open to the sold out game.

Inbetween two large metal stands is the banked track. It’s not painted, and the yellowish protective foam that covers the railings is taped on. Fans pile into their seats with homemade signs. A group friends cheer on their friend with the poster, “I ♥ Adolf Hitzer.” At the top of the track, there’s an elevated stage for the band Hard Copy Rebels. They’re a five man rock band dressed in tan police uniforms, fake mustaches, and shorts almost as short as those the girls are wearing. In their repetoire are covers of Taylor Swift, Miley Cyrus, and Katie Perry. They play while the girls get ready to skate. The lights turn off, every one cheers, and all the people that were standing by the bar area move to the benches with their drinks. A spotlight illuminates the track. The Terminal Island Tootsies enter the track. They skate around the ring waving to the audience as the announcer introduces the players. As the next team is introduced, the song "Play That Funky Music" by Wild Cherry blasts out of the speakers. The Fourth Street Retro Rollers dance into the ring sporting big headphones and groovy moves. The uniforms are less like sports wear and more like costumes. The Retro Rollers are wearing brown, orange, and yellow colored tank-tops and shorts straight out of the 60s. The Tootsies wear short red, white, and blue sailor outfits with little white hats before replacing them with red helmets. It’s clear the captains of the teams, and co-founders of the league, Estro Jen and Diesel aim to entertain the crowd. From the music to the outfits to the comedic announcers, its a show. Estro Jen tells the Long Beach Gazette she wants it to be “a production.”

However, the production doesn’t go without technical difficulties. As their track moneky crew works out the kinks, two male coaches, one of which is Quadzilla, challenge each other to a skate off. They each take turns skating around the track doing tricks. Every trick more daring than the next has the crowd on the edge of their uncomfortable metal seats. Unable to distinguish a clear winner, they decide to settle it with an Evil Knievel inspired death trick. They go over to their team benches and pick out three girls, two refs, and a manager. They direct them to lay down side-by-side on the track. Quadzilla pumps up the crowd waving his arms in the air. The excited crowd shouts and claps. There’s a drumroll. He starts skating away from the six stiff bodies on the track. As he circles back towards them, people get on their feet. Six feet away from the daredevils laying on the floor, he stops building up speed and steadies his feet. He crouches down to prepare for flight. Some people in the audience cover their eyes. He jumps. The drumroll and gasps are the only sounds filling the dome as he cuts through the air. He lands safely a few feet away from Terminal Tootsie, Ida Capitate's chest. The crowd screams and applaudes. After a short victory lap, he riles up the crowd for the coach of the T.I.T.s. Encouraged by their cheers, he starts off around the track. As he rounds the last turn before the jump, Quadzilla slips onto the end of the line. Just seconds before he jumps, now there's seven people on the ground. He clears it with easy. They claim dual-winnership and raise their clasped hands into the air as the crowd cheers. Shortly after, at half-time, the band turned out more amusing covers as the lead singer went into the crowd to give lap dances. Though the derby was good, it was more of an aspect to the show, than the entire focus.

For Orange County, roller derby is a sport. It’s not a show. While the girls don’t mind entertaining the crowd with exciting jams, they don’t want to detract from the sport of derby with costumes and side shows. They’ve trained hard and want derby to exhibit their athletesism. On May 7, the OC Roller Girls were ready to premiere their track. They dissembled the entire 101x57 foot structure and moved all 44 sections from Huntington Beach to the Anaheim Convention Center to reassemble it. Derby girls Bout Bot and Captain Holler wait by open doors to receive the crowd. The age of the crowd varies from parents who have brought their babies to 80 year olds who have come to watch derby as they did in their youth. The brightly lit stadium displays the black and orange colors worn by members of the crowd that sprinkle the cushioned blue seats. They don’t fill the 7,500 available seats, but the audience of a few hundred people waits with the same anticipation as a sold out crowd. A seven piece reggae band fills the time before the bout. The teams enter and line up along the center of the track kneeling on one knee. A row of neatly arranged orange shirts next to a row of perfectly placed black shirts. The announcer describes the origins of OC Roller Girls. He asks Mia to stand up and take a bow for her contributions. Her big bright smile can be seen from the top of the stands. She waves. The announcer gives special mention to two members of the crowd. One, named John Hall, was an original member of the 1960s Los Angeles Thunderbirds. The other, a security worker at the Convention Center named Ruby Gaither, was a derby girl in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. The crowd applauds. The announcer asks everyone to please stand and salute the flag as derby girl Chick Norris sings the national anthem. The audience cheers as she holds the last note of, “And the land of the brave.” Jammers for Orange Whip and The Traffic Jammers assume their position behind the blockers. The bout begins.

People go up to Ruby asking for autographs. A tall, boisterous African American women with curly hair and a big smile, Ruby is glowing with excitement. She tells stories about traveling with the international derby team to Japan and Hawaii. She’s photocopied and autographed pictures from her roller derby photo album and hands them out to whoever comes to talk with her. From the rules to the amount of padding, Ruby can’t believe how much derby has changed, “We wore--you know, the pants and the pads on the butt, and on the hips, and maybe little knee pads. That was the extent of our padding. So it really hurt when you fell!” She didn’t wear a helmet, elbow pads, or a mouthguard. She remembers getting injured fondly, “Oh lord, yes.” She laughs, “I had a dislocated back. I broke my arm and a wrist. And you know the track? If you get a bruise, it buurns--when water hit it--it burns like hell! It felt like you put peroxide on it. But it burns, like, so bad. Oh yeah, ooooooh yeah!” She started playing derby in 1964 and was on and off for the next two decades. “I was number 36,” she says showing a picture of her old uniform. She can’t deicde what her favorite position was. She liked being a jammer so she could score points, but she also liked being a blocker. “I liked to play as a blocker because I could knock ‘em into the rail and knock ‘em out--and see, that’s what the fans like. You know, whenever you can use the fans to interact with.” She didn’t get paid much to play derby, but she loved it. After having her two sons, she decided it was time to give derby up, but it was always a part of who she was. The years that derby took her to Tokyo and Hawaii were the most exciting times of her life. When she talks about it, tears fill up in her eyes. When asked why she loves derby so much, she responds the same way as Mia. She looks off into the distance for a moment, thinking about the question, then turns back shrugging her shoulders and smiling, “Because it’s fun!”

At half-time the girls go up to their friends and family. Mia picks up her daughter Bella and poses for pictures. At 17 months, Bella already has a pair of skates. Mia hopes one day she’ll grow up to be an amazing skater.

The bout was organized and went without technical difficulties. The only scary moment came in the second half. Ruby Rocker, who got into derby after writing an article on the OC Derby Girls while attending Cal State Fullerton, took a hard fall. The girls behind her were unable to stop in time and tripped over her, ramming their skates into her ribs. The domino effect resulted a pile up of girls. Its a common occurance in derby, but this time, Ruby wasn’t getting up. As the rest of the pack stood up and took off, Ruby laid on the track curled up, clutching her ribs. Girls on the opposing team dragged her off the track and over to their bench. They call a time out. After a few tears, she dries off her eyes and makes her way back to her team’s bench. The team chiropractor, Dr. Marta L. Collatta, checks her out asking how she feels. Ruby lies and says she's fine, “I didn’t want them to take me out. I wanted to keep playing!” Her coach allows her to play. Though she continues to grab her ribs during resting periods, she won't let her injury take her out of the game. She took two practices to recover, but was back to skating in a week.

The final score of the bout was 124, Orange Whip, to 112, Traffic Jammers. The girls cheer along with the crowd as the last whistle is blown. They have successfully brought banked track roller derby back to Orange County. They accomplished something no one had in over 30 years. The girls, the refs, the coaches, and the managers piled onto the track. Hugging, with tears in their eyes, they pose for pictures.

Reporting Notes:

Three 3 hour practices

One 4 hour LBRD bout

One 4 hour OCRG bout

One 25 minute interview with Mia Roller a.k.a Elena Parra

One 15 minute interview with Ruby Rocker a.k.a Sarah Cruz

One 20 minute interview with Ruby Gaither

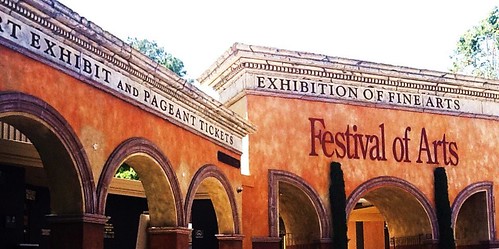

Despite Economic Pressures, Local Artist Keeps Laguna Culture Alive

Despite Economic Pressures, Local Artist Keeps Laguna Culture Alive